By Cory

Flattening Yield Curve is Good

The post below is from our friend Axel Merk from Merk Investments. We have been talking about rising yields but still a flattening of the yield curve. Axel breaks down what it all means and more importantly what we should be watching in terms of the steepness and economy.

Click here to visit the Merk Investments website.

…Here’s the post…

In recent months, pundits have cautioned about a flattening yield curve, suggesting it may signal the end of the economic expansion, the end of the bull market, possibly even the end of the world as we know it. There’s plenty to worry about in the markets, but in the spirit that knowledge is the enemy of ignorance, let’s clear up some myths.

First, what is yield curve steepness? It reflects the relationship between the short end and long end of the yield curve. Got it? Okay, let’s dissect this jargon:

- The “short end” of the yield curve refers to shorter-term interest rates. This could be the current Federal Funds Target that the Federal Reserve Open Market Committee (FOMC) controls and is colloquially referred to as the current interest rate; more broadly, it is referring to yields on Treasury securities of a few years. In the context of our discussion, many refer to 2 years or 3 years (although some go out as far as 5 years).

- The “long end” of the yield curve refers to longer-term interest rates. This is often the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond, sometimes the 30-year Treasury bond (also called the “long bond”).

- For some context, before the financial crisis, it was generally believed the Fed controls the short-end of the yield curve, whereas the long-end of the yield curve is more of a reflection of the longer run potential of the economy and longer run inflation expectations. Since the financial crisis, there’s a plethora of opinions to what extent the Fed’s quantitative easing (QE) has influenced longer-term rates.

- The steepness of the yield curve is the difference between the yield at the long end of the yield curve and the short end of the yield curve. The 2s10s yield curve, for example, is the yield of the 10-year bond minus 2-year Treasuries plotted across time.

- The yield curve is steep when short-term rates are lower than long-term rates; it is “flat” when they are the same; and the yield curve is inverted when short-term rates are higher than long-term rates.

- In a classic banking model, banks borrow money short-term to make long-term loans. As such, when the yield curve is steep, the more money banks lend, the more money they make (assuming their borrowers don’t default); as the yield curve flattens and potentially inverts, margins could get squeezed and potentially become negative. It’s a tad more complicated than that because private borrowers pay a higher rate than that available to the government. An inverted yield curve may suggest that the Federal Reserve wants to slow the economy down.

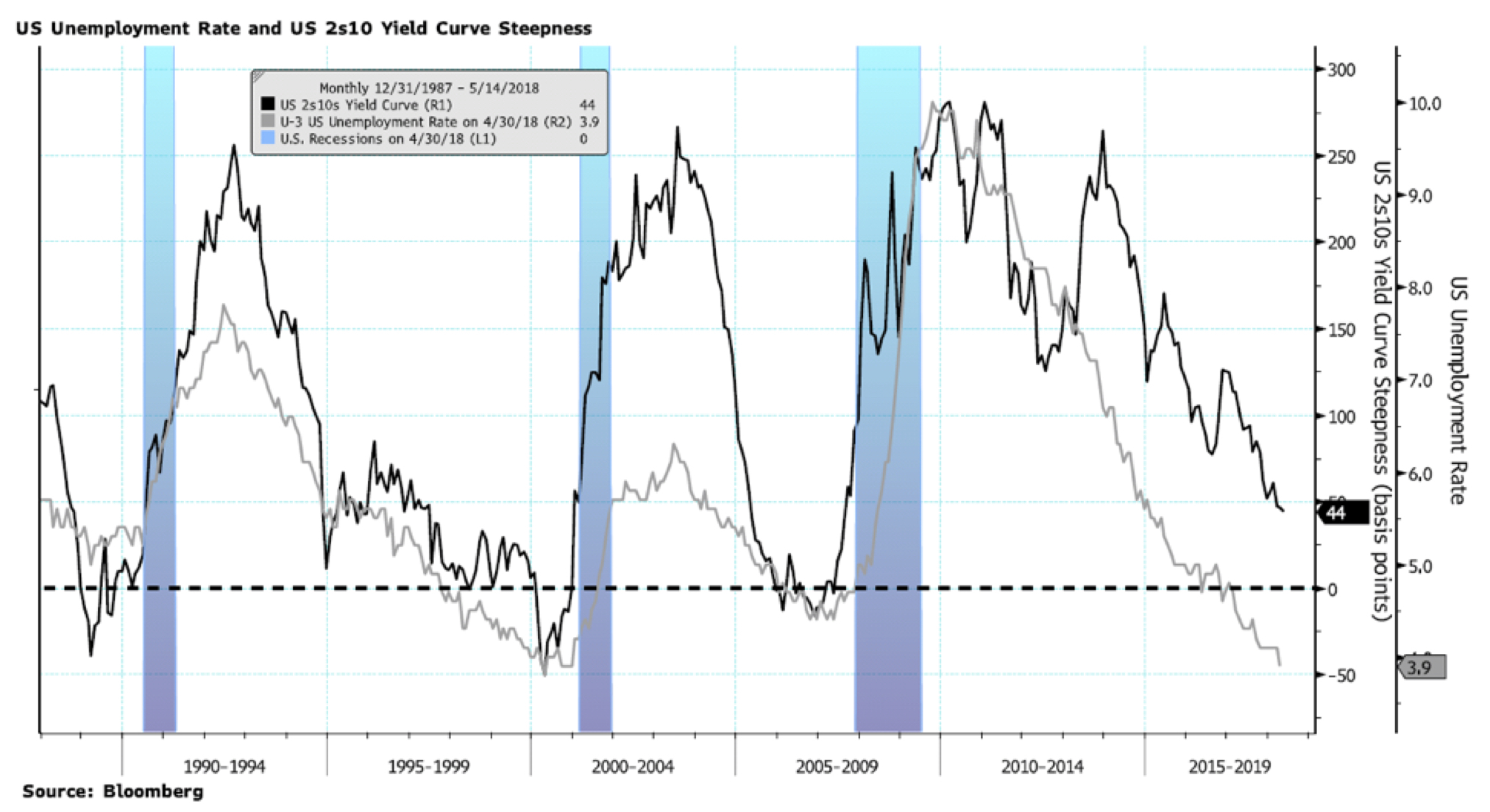

With this context, please look at the chart above which also shows the unemployment rate and recessions. The yield curve has been flattening since 2010; if you listen to financial media, you might think it’s a new development. The fact that the yield curve is flattening or at a relatively flat level does not really mean anything by itself, for example the yield curve was relatively flat in the second half of the 1990s and economic growth remained strong for years. The advertising-based media model means that media outlets want your attention all the time, and therefore they tend to generate fear inducing headlines like “US Treasury yield curve hasn’t been this flat since 2007” just to get you to click.

Ahead of the financial crisis in 2007, the yield curve was actually steepening, not flattening. In our assessment, the proper comparison between now and the prior cycle is actually 2005, not 2007. The point is that you often see the yield curve actually steepening within the year prior to a recession, having been inverted prior to the steepening. Please see the black line on the above chart.

Tying it back to markets, the S&P 500 topped in October 2007, well after inversion and while yield curve steepening was already underway.

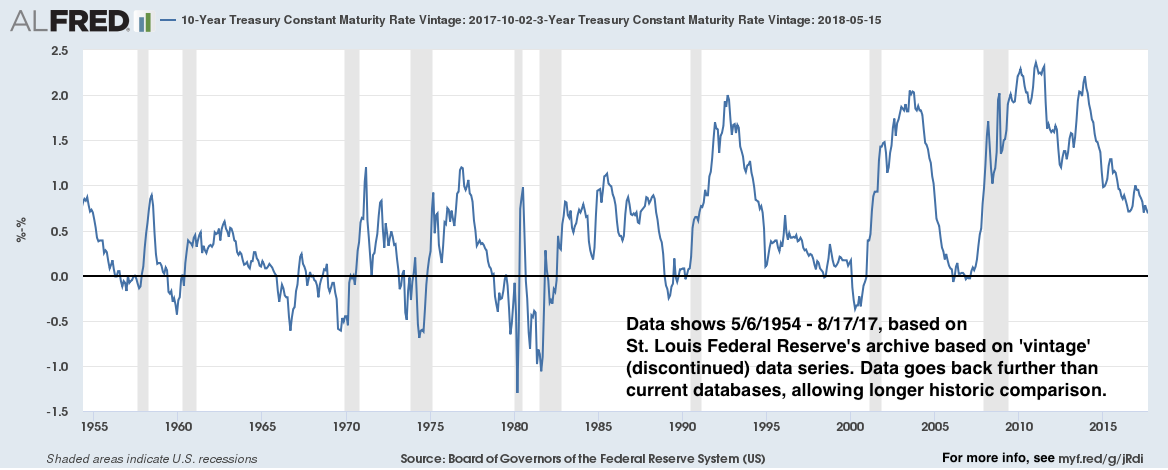

Taking a longer-term perspective: for the nine recessions since 1954, all were preceded by a 3s10s inversion, the average length of time before the subsequent recession was 15 months, with 10 months being the shortest amount of time, and 20 months the longest. There were four false signals: in 1965, in 1967, in 1971 and in 1998. So historically a 3s10s inversion was a necessary but not sufficient signal for a recession, and there was at least a 10-month lag before the subsequent recession started.

Even given the historical evidence, it is certainly possible that the next recession will start without the yield curve inverting ahead of time. However, if history is any guide, the balance of probabilities seems it suggest that inversion will happen again prior to the next recession. But that doesn’t mean a flattening yield curve is an imminent warning sign. Instead, in today’s context, we believe a better characterization may be that the flattening yield curve is a reflection that the Fed believes the brakes ought to be applied (even if they want to do so ‘gradually’) to a strong economy.

Will it end in a recession? Of course. The probability of a recession is 100%, as J.P. Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon quips; the question is not whether a recession will happen, but when.

In taking the yield curve steepness as a model, we should take note of any inversion. That said, we would likely be far more concerned about a downturn in the economy should the yield curve steepen once again after the inversion has occurred.

For context, the US 10 year yield is, as of this writing, just under 3%; it hit a low of 1.36% in 2016. The Fed funds rate right now is set to be between 1.50% and …read more

From:: The Korelin Economic Report