Global miners will have to get ready

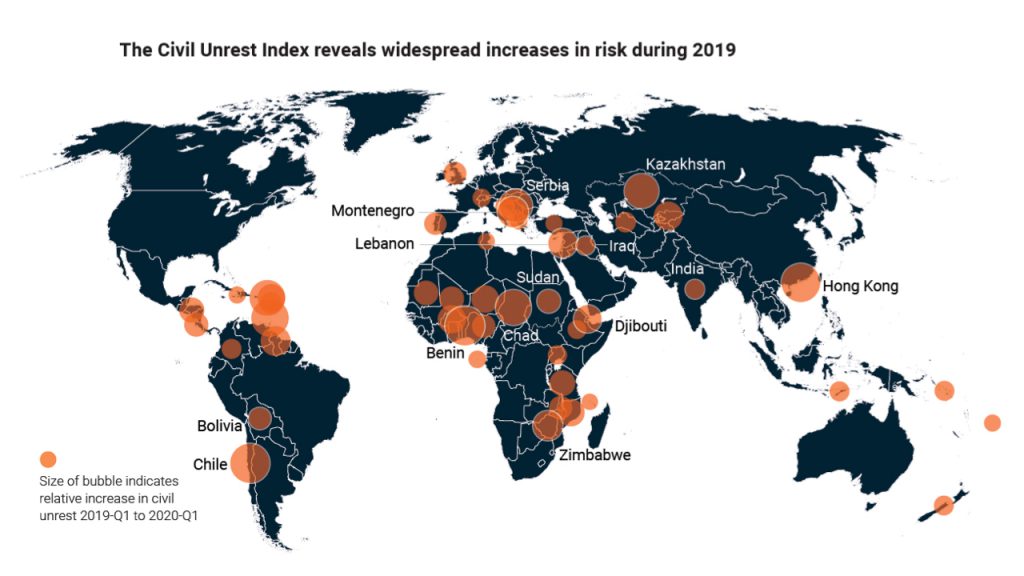

to deal with the increasing threat from civil unrest, following last year’s succession

of dramatic — and in several cases unforeseen — social explosions in

almost 50 countries, including highly popular mining jurisdictions such as Chile,

Mali, Guinea, Congo and Zimbabwe.

According to risk consultancy Verisk

Maplecroft’s quarterly civil unrest index, released on Thursday, turmoil

will linger in 2020, as most nations experiencing ongoing bursts of public

discontent lack the tools and ability to handle them.

The experts foresee as many as 75 countries having to deal with soaring public rage over a variety of topics, including economic inequality and political roguery during the next six months.

Other jurisdictions, such as Hong Kong and Chile, which saw the greatest increases in risk over the last year, are unlikely to improve over the next two years, Verisk Maplecroft’s predicts.

As a result, the number of extremely

risky countries in the Civil Unrest Index jumped by 66.7%; from 12 in 2019 to

20 by early 2020.

An ‘extreme risk’ rating in the

index, which measures the risks to business, reflects the highest possible

threat of transport disruption, damage to company assets and physical risks to

employees from violent unrest. Most sectors, ranging across mining, energy,

tourism, retail and financial services, have felt the impacts over the past

year.

The resulting disruption to business, national economies and investment worldwide has totalled in the billions of US dollars, the consultancy says, citing Chile as an example. The first month of unrest in the copper-rich country caused an estimated $4.6 billion worth of infrastructure damage, and cost the Chilean economy around $3 billion, or 1.1% of its GDP, Verisk Maplecroft notes.

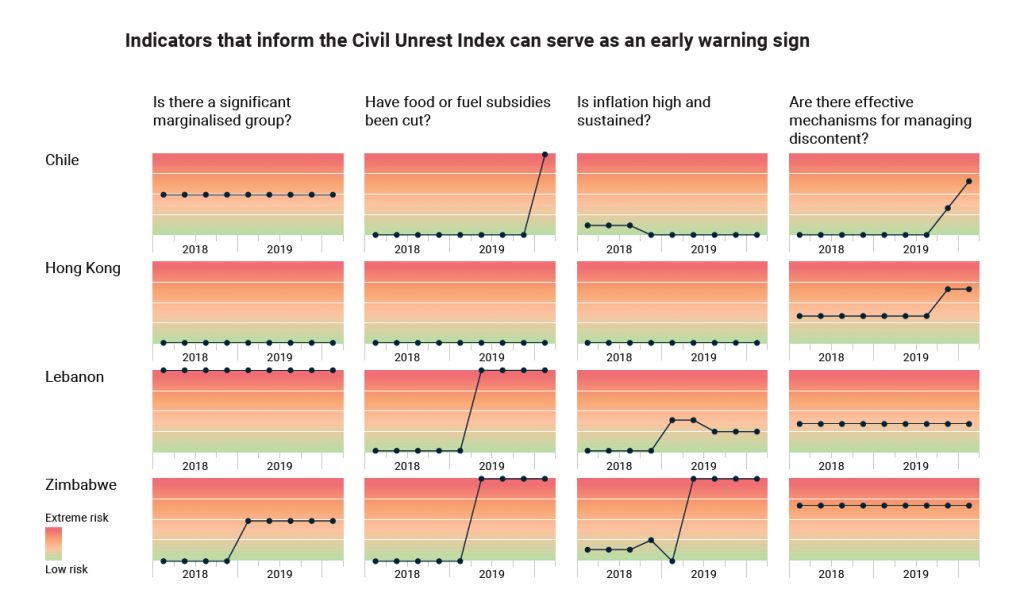

The consultancy detected that a

deterioration in some risk factors could serve as an early warning sign in

certain jurisdictions. Out of the 11 elements considered in the Civil Unrest

Index, subsidy cuts were the single biggest indicator that the risk of civil

unrest was growing in Chile, Lebanon and Zimbabwe.

Inflation and the weakening of mechanisms that allow the channelling of discontent before it erupts into unrest also played a role, Verisk Maplecroft says, particularly in Chile, Hong Kong and Zimbabwe.

With protests continuing to rage across the globe, the consultancy expects both the intensity of civil unrest, as well as the total number of countries experiencing disruption, to rise over the coming year.