Mining the sea floor opens a vast source of key metals needed for clean energy, but should not start until a full evaluation of likely environmental impacts can be made, a report commissioned by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) shows.

The group of academics and environmentalists believe an international moratorium on deep-sea mining is urgently needed. Otherwise, they warn of likely irreversible damage to global aquatic ecosystems.

In their study, published on Wednesday, the experts note that copper, rare earths and iron ore were the resources that piqued miners’ original interest in exploring the seafloor.

In the past two years, however, minerals needed for a green energy transition, including cobalt and nickel, whose demand could exceed current production rates by 2030, are driving the rapidly rising interest in the activity.

There have been some attempts to regulate the emerging industry. Two years ago, the European Parliament called for a ban on seabed mining until the environmental impacts and risks of disturbing unique deep-sea ecosystems are understood.

In the resolution, it also urged the European Commission to persuade member states to stop sponsoring and subsidizing licenses to explore and exploit the seabed in international waters as well as within their own territories.

Shortly after, an international team of researchers published a set of criteria to help the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN body made up of 168 countries, protect biodiversity from deep-sea mining activities.

The ISA was scheduled to discuss regulation that could allow deep seabed mining in July. The annual assembly, however, has delayed to October because of the covid-19 pandemic.

Seafloor nodules

According to the US Geological Survey, as the deep-sea accounts for more than half the world’s surface, its riches are several times higher than those found in all land reserves combined.

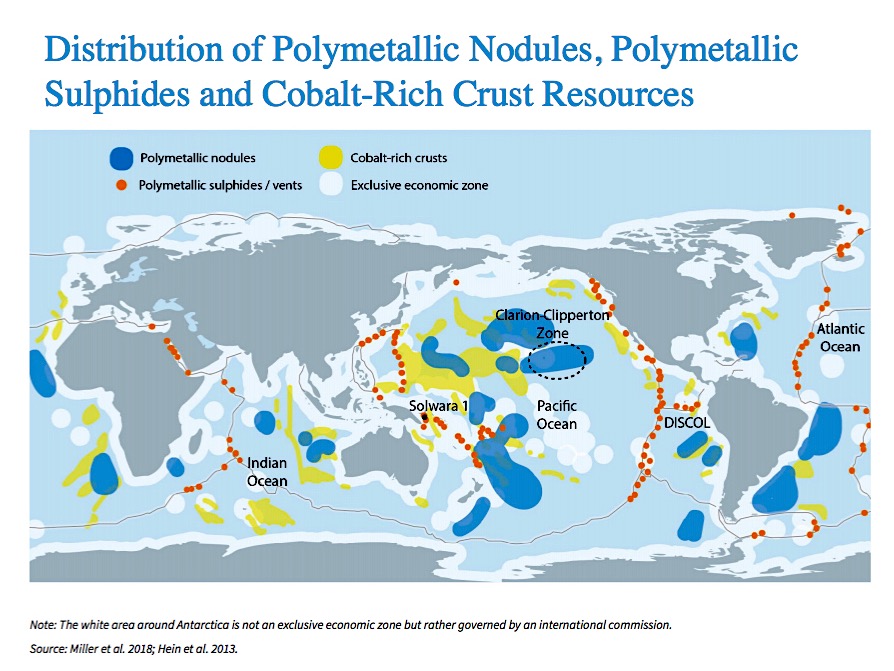

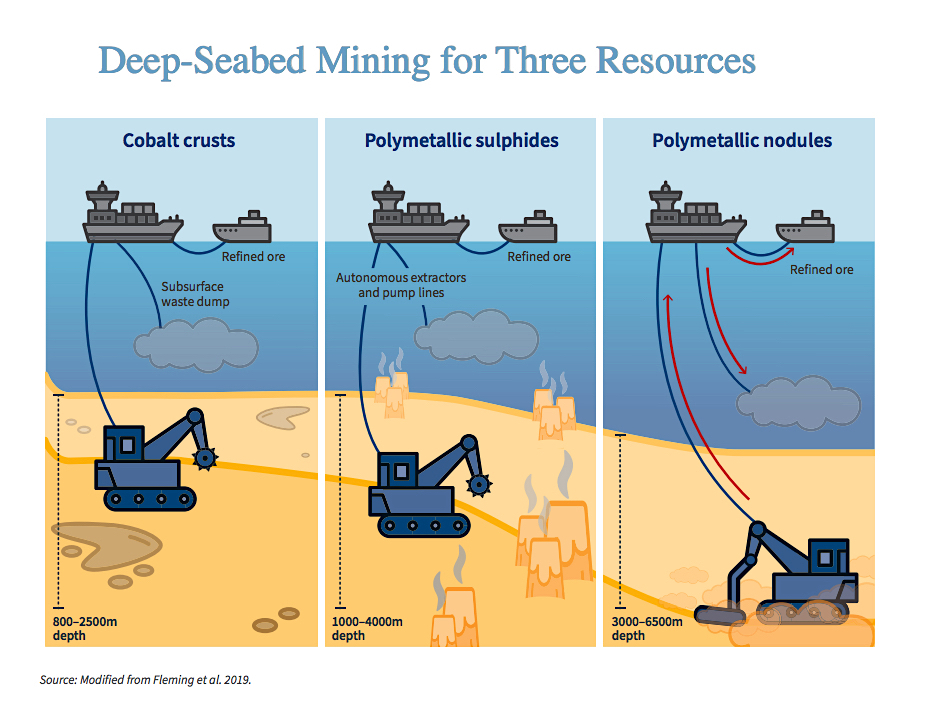

The main target of companies planning to mine underwater are polymetallic nodules. Those potato-sized metals-rich rocks, which lie in a shallow layer of mud on the seafloor, are rich in cobalt, nickel, copper, manganese and rare earths.

Scientists and explorers have also identified cobalt-rich crusts, located shallower than nodules and sulphates.

Echoing dozens of academic institutions and non-profit organizations, the authors of today’s report call for further research to fill gaps in knowledge before any seabed mining is allowed. It also argues for the need of setting protected zones across all ocean regions under the ISA’s jurisdiction.

The report also recommends countries should encourage the recycling of battery metals to reduce the need of finding new supplies.

The Ocean Panel brings together heads of state from 14 countries, including Australia, Canada, Chile, Kenya, Japan and Norway.