The collapse of the copper price and the containment measures taken for the coronavirus pandemic, are posing a significant risk to global copper mine supply and project development, Nick Pickens, research director at Wood Mackenzie said in a note this week.

Day-by-day, mining companies are announcing revised plans to comply with new restrictions.

“For now, temporary closures will be absorbed by our mine disruption allowance,” Pickens said.

“In a scenario where there are wholesale closures of mines in Peru and Chile for 15 days, we would see 1.5% wiped from global annual supply. It would take 45 days to reach our full-year mine disruption allowance.”

“In a scenario where there are wholesale closures of mines in Peru and Chile for 15 days, we would see 1.5% wiped from global annual supply”

Nick Pickens, research director, Wood Mackenzie

“At this stage, we are not assuming mine supply from these countries will stop in its entirety. However, we believe there is a significant risk that disruptions will escalate, and breach 5% this year.”

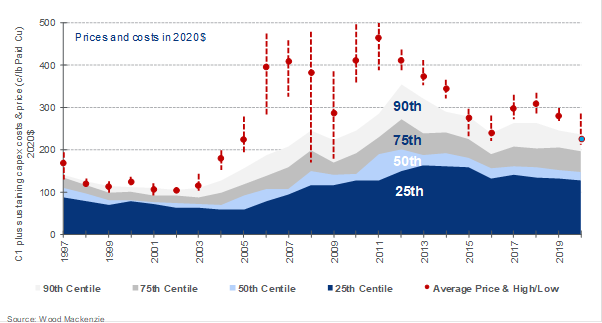

Low prices could hamper mine restarts and new projects. The copper price is currently trading below the 90th centile of the industry cost curve (223 c/lb). Temporary closures and construction deferrals have accelerated due to virus containment. However, a sustained period of lower prices could make these more permanent.

Cost deflation will help to ease margins, Pickens said.

“Our mark-to market analysis suggests that at current market oil prices and exchange rates, the 90th centile of the C1 plus capex cost curve will fall by nearly 25 c/lb when compared to 2019. Furthermore, a prolonged period of lower average oil prices will have a more extensive deflationary influence for other raw material costs, and the impact could be more significant.”

Supply disruptions, directly relating to coronavirus

In recent days, the reach of coronavirus has rapidly expanded from key regions of copper demand – China and Europe, to key regions of supply – the Americas. Peru has enforced widespread quarantine, and some mines are now thought to be on temporary care and maintenance.

“In Chile, a state of catastrophe has been

declared. We have also seen temporary cutbacks and risks to suspensions in Canada,

the DR Congo and Australia,” Pickens said.

In Peru, the government has taken measures to prevent the spread of the pandemic throughout the mining industry. Mining companies have been asked to only mobilise critical employees to mine sites, to implement an emergency plan adapted to the circumstances, and to ensure health protection for a 15-day period, from 19 March.

Critical employees might comprise those who work

in environmental or safety functions such as water treatment plants, ground

stability, tailings monitoring, underground ventilation and security, Pickens

said.

This would mean that mining operations would

effectively go under care and maintenance for 15 days. Large operations that

have followed this measure include Cerro Verde and Constancia.

Some mining companies, such as Buenaventura, have

implemented these measures at all operations. However, other companies, due to

their remote location and capabilities to ensure the health of their employee,

have decided to just keep slow down production.

Chile has also stepped up its response. The government declared a “state of catastrophe” starting March 19, as the confirmed cases of coronavirus continued to rise.

“This measure gives the government the capability

to control the food and medical supply chains and distribution, border

protection, and to enforce curfews and restrict social gatherings,” Pickens

said.

“Immediately after the announcement, Codelco said

it would maintain “operational continuity” for 15 days in all is units.

Meanwhile, we understand Spence and Escondida’s union has asked BHP to

implement stricter measures to ensure the health of its employees or shutdown,”

he added.

What does this mean for global supply?

The most noteworthy announcements to date, in

terms of significance to the global copper market, have been from authorities

in Chile and Peru, who are both pointing to a 15-day disruption. All out

closures in Peru and Chile for 15 days, would see 1.5% wiped from global annual

supply, Pickens asserted.

The containment of coronavirus is also affecting construction of new projects, with several major producers announcing they are slowing or temporarily stopping development

“While this is significant, it would be absorbed

by our disruption allowance. It is also not likely to be long enough to trigger

force majeure on shipments.”

“In our opinion, the restrictions will need to be in place longer than 15 days. It would take 45 days to disrupt 5% of supply from these countries, equivalent to our full-year disruption allowance of just over 1.0 Mt,” Pickens said.

“At this stage, we are not assuming mine supply from these countries will stop in its entirety. The early indications are that some major companies in Peru and Chile are managing to produce under the restrictions.”

“However, there is a worse-case scenario to consider. If the need for containment leads to wholesale lockdown of mine sites, and this Latin America disruption is replicated in Africa, North America and Australia, this would have catastrophic consequences for global copper mine supply,” Pickens said.

“This is not currently, our base case assumption, but as we publish this Insight, there are clear signs that measures to contain the virus are likely to intensify over the coming days and weeks.”

Mine supply beyond 2020: Project delays put future supply growth at risk

The containment of coronavirus is also affecting construction of new projects, with several major producers announcing they are slowing or temporarily stopping development.

A third of mine supply growth over the next three years will be from Peru (Quellaveco and Mina Justa) and Chile (Quebrada Blanca Phase 2 “QB2” and Spence). Elsewhere, greenfield and brownfield projects in Indonesia (Grasberg Block Cave), Mongolia (Oyu Tolgoi underground) and DR Congo (Kamoa-Kakula) will also contribute significant volumes.

“However, within the last week, at least three of

these projects have either stopped or slowed construction. Anglo American has

announced that Quellaveco construction has slowed, under the 15-day national

quarantine measures taken in Peru,” Pickens said.

Teck has suspended construction activities at QB2 project in Chile for an initial two-week period. In Mongolia, there are reports that work has slowed at Oyu Tolgoi, due to the restrictions placed by the government. Combined, these projects account for a third of the total net growth expected over the next three years.

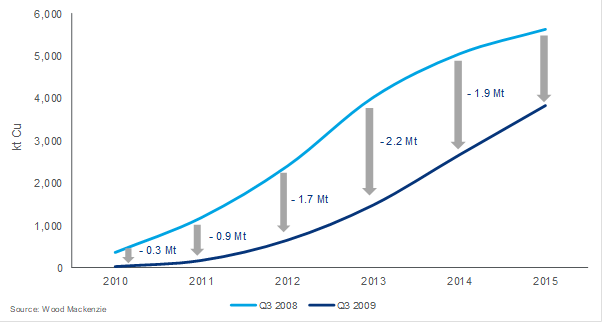

“The current supply-side outlook is analogous to the market in 2008/09. At the start of 2008, there was healthy pipeline of near-term projects, in our probable and highly probable (now included in our base case) categories. But a severe demand shock, brought about by the GFC, triggered project delays. During the 12 months between Q3

2008 and Q3 2009, we estimate the mining industry

deferred up to 2.2 Mt/a of new copper supply. While projects eventually hit the

market, they were later than expected. This undoubtedly contributed to the

tighter market and high prices experienced in 2010 and 2011, once the market

recovered,” Pickens said.

Highly probable & probable project deferrals: Q3 2008 project pipeline versus Q3 2009 project pipeline:

Supply-side response to price:

The LME cash price closed at $4,855/t (220 c/lb)

on March 20, falling 15 % in just a week, and 25% since the start of the

year. The price decline began on 13 March, just after the World Health

Organisation (WHO) declared a global pandemic.

“Since then, hopes that containment in China,

followed by government stimulus could be the catalyst for a V-shaped recovery,

have faded fast,” Pickens said.

“With demand contracting and prices plummeting,

an economic supply response now seems likely. The disruption caused by virus

containment has been the catalyst for a quicker reaction than is typical by the

mining industry in a downturn,” Pickens said.

“So far, the covid-19 closures are temporary. However, with prices low, the decision to restart will become difficult for some producers. Furthermore, the longer prices stay depressed, marginal mining operations, not currently disrupted by coronavirus, may be forced to cut production regardless. History tells us, these cuts take a little longer to occur, as operators first cut back on non-essential capex.”

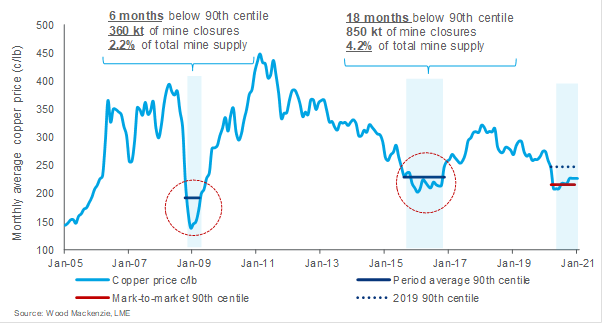

“Over the last decade, there have been two periods of price-related mine closures. The first was in 2008/09 demand shock during the GFC. The second was in 2015/16, when strong mine supply growth and weaker demand prompted a significant price decline”

Nick Pickens, Research Director, wood mackenzie

“Over the last decade, there have been two

periods of price-related mine closures. The first was in 2008/09 demand shock

during the GFC. The second was in 2015/16, when strong mine supply growth and

weaker demand prompted a significant price decline,” Pickens said.

In 2008/09 prices crashed below the 90th centile

for a period of six months, reaching well into the third quartile for short

periods. This resulted in around and 2.2% of price related closures. In

2015/16, the copper price decline was supply driven and longer lasting. Prices

were below the 90th centile for 18 months, with 4.2% of annual global supply

removed from the market.

“The impact on supply could be less than previous

downturns, owing to a lower starting point,” Pickens said. “We expect total

refined production to decline this year. This in part due to a decline in mine

supply, but also due to the fall in production from scrap and blister units. As

a result, we estimate a supply cut of only 200 kt, beyond the normal 5%

disruption, would be enough to bring the refined market back to our long-term

equilibrium.”

Previous supply-side responses to lower prices:

“We expect average annual prices will be

supported at around $4,850/t (220 c/lb) over the remainder of the year.

This assumes that prices will average out at the 90th centile

of the cost curve, which is now significantly lower than the 2019 level on

account of a lower oil price and weaker producer currencies,” Pickens said. “However,

history also tells us that in a demand shock, prices could drop hit lows as

60-70th centile,

below <200 c/lb for short periods.”

In 2008/09, prices fell below the 90th centile

for a period of six months, reaching well into the third quartile for short

periods. Meanwhile, in 2015/16 prices were lower for longer (18 months), but

did not cut quite as deep, reaching closer to the 80th centile.

Historic copper price and copper mine cost centiles, C1 plus sustaining capex (2020$)

Fuel prices and exchange rates have reduced costs, and the price floor:

The oil price crashed in early March, driven by

weak demand and rapidly increasing supply from Saudi Arabia. The result has

been a 50% decrease in Brent oil price to less than US$30/bbl, Pickens

reported.

On average, fuel represents 7% of overall

mine-site costs. A 50% decline in oil prices, from US$64/bbl (Brent) in 2019 to

US$30/bbl in the current market is expected to reduce average minesite costs by

around 5 c/lb.

“However, we expect a prolonged period of lower average oil prices will have a more extensive deflationary influence for other raw material costs,” Pickens said.

“Analysis of historical performance between the price of oil and the cost of energy, services and consumables, suggests that these components could impact average costs by a further 5 c/lb. The combined direct and indirect sensitivity is therefore 3 c/lb per $10/bbl of oil.”

But it’s not just the oil price that is reducing costs, he asserted. In most major copper-producing countries, local currency has depreciated against the US dollar, when compared to 2019 averages. The top ten producing countries (along with US output) account for 75% of global copper mine production in 2019 and, on average, currencies in these regions have depreciated by over 10%.

“Our mark-to-market analysis suggests at current

market prices, the 90th centile of the C1 plus capex cost curve

will fall by nearly 25 c/lb to 223 c/lb. Furthermore, a prolonged period of

lower average oil prices will have a more extensive deflationary influence for

other raw material costs, and the impact could be more significant,” Pickens

said.