Rio Tinto’s new carbon emissions reduction targets have triggered heated criticism from some investors and environmental groups rather than appeased them, with a group led by a Friends of the Earth’s subsidiary tabling a shareholder motion to improve what it calls “weak” climate goals.

The world’s second largest miner last week vowed to spend $1

billion over the next five years to reduce its carbon footprint and have “net

zero” greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

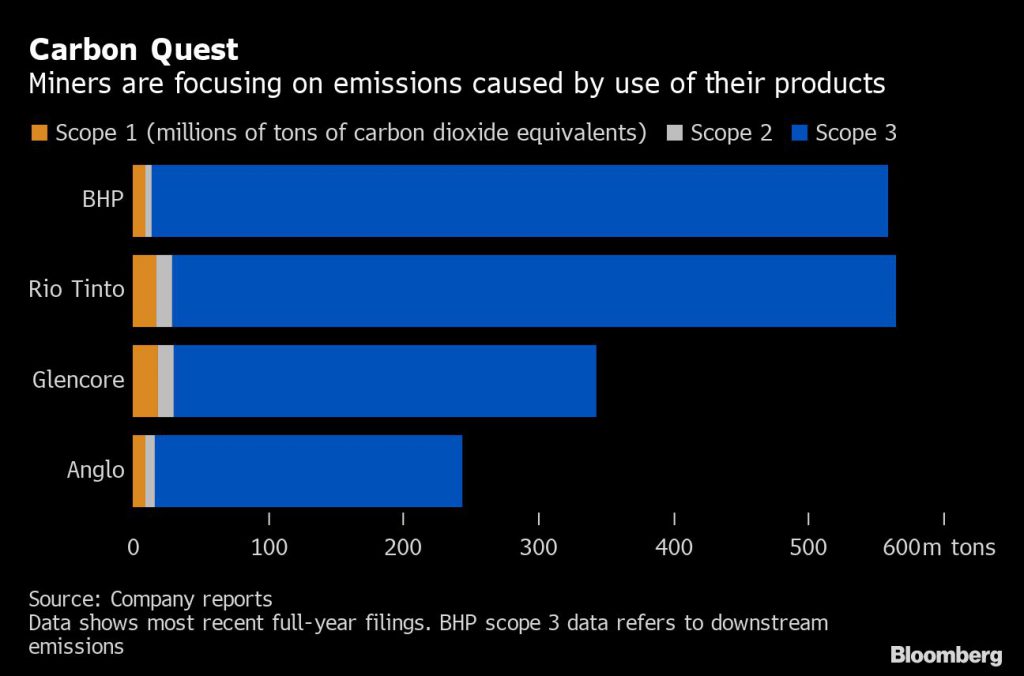

Rio also said its total Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions (indirect emissions from the generation of purchased energy consumed by a company, such as electricity) would 15% lower by 2030 than 2018 levels.

“Rio Tinto is essentially telling its shareholders it is aware of a massive financial liability sitting on its books, but isn’t planning to manage that risk down.”

Market Force’s Executive director, Julien Vincent.

The no emissions goal would be easier to achieve for Rio

Tinto than other global miners, such as rival BHP (ASX, LON, NYSE: BHP) because

it does not mine coal or oil.

The company, however, did not set a target to reduce

so-called “Scope 3” emissions — those produced when customers burn or

process a company’s raw materials.

Market Force, a subsidiary of activist investor Friends of

the Earth, said the company’s announcement is a “simply a reflection of

business-as-usual” energy cost savings and efficiency measures.

“Rio Tinto is essentially telling its shareholders it is aware of a massive financial liability sitting on its books, but isn’t planning to manage that risk down,” Executive director, Julien Vincent, told FT.com.

He noted that Rio’s absolute emissions would have to decline

30% in the next decade to hit the “well below” 2°C global pre-industrial levels

outlined in the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

UBS analyst Glyn Lawcock said the group could almost

instantly achieve the 2030 target if it sold or closed its coal-fired alumina

refineries and aluminum smelters in Australia.

“We couldn’t help but notice that the closure of Pacific Aluminium alone would reduce emissions by (about) 25%,”’ he said in a note.

“Maybe this is the elegant solution to Rio’s desire to

reduce carbon dioxide as well as lifting margins within the aluminium business

unit.”

For Julian Kettle, Wood Mackenzie vice chairman of metals

and mining, Rio’s plans to decarbonize its globe-spanning operations are a

“small but significant” step in the right direction.

“Setting Rio Tinto’s $1bn in context, this represents just

16% of the dividend it distributed in 2019 or just under 5% of its reported

EBITDA of $21.2bn for the same year,” Kettle said.

“Put another way, on a 100% basis, Rio Tinto reported iron

ore production of 327Mt in 2019. A $1bn dollar green investment, while

laudable, could be funded by a 30c/tonne rise in the iron ore price. The

industry needs to do much more,” he noted.

Rio’s bulk of earnings comes iron ore, its main commodity

and a key ingredient for steelmaking. The highly polluting industry process

involves adding coking coal to make carbon steel and is responsible for up to

9% of global greenhouse emissions.