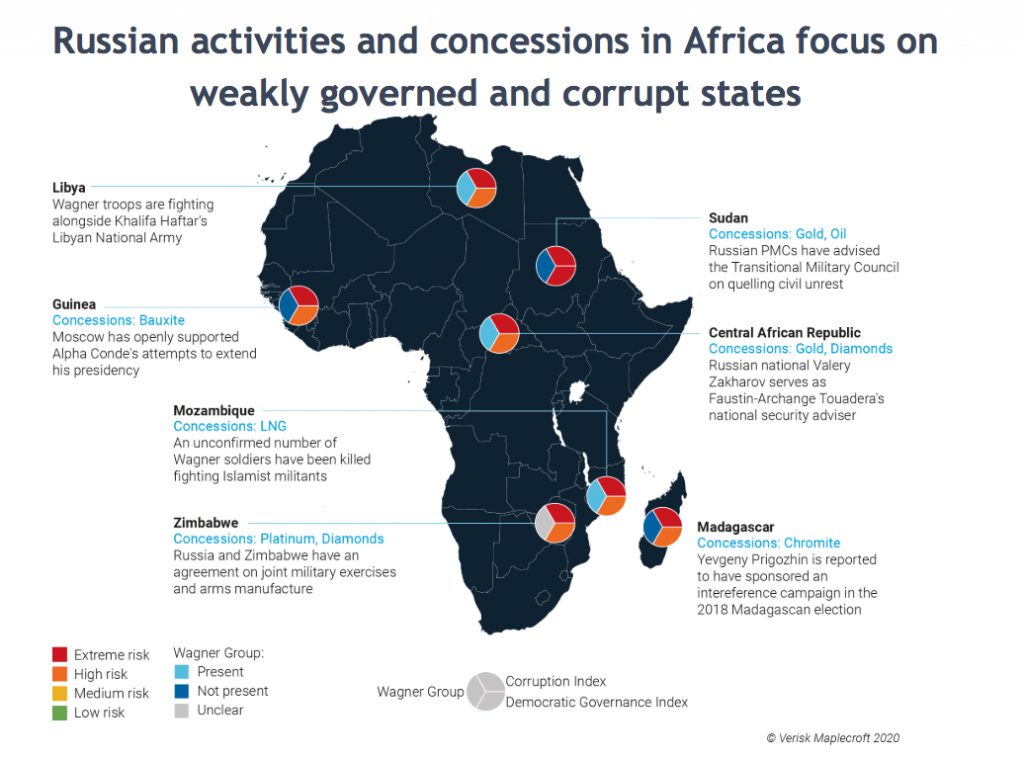

While Russia has been playing for power in Africa in recent years by sending arms, offering mercenaries and cinching mining deals, the foundations of Moscow’s claim to renewed global influence are shaky at best, a new political risks report claims.

The reality, says Daragh

McDowell, analyst at consultancy Verisk Maplecroft, is that

the Kremlin is putting profit ahead of power, and is relying on private

military contractors (PMCs) and “political technologists” to project its

influence on the world.

Russia, however, can only use such deployments in states with weak democratic and legal norms, and is doing so primarily to secure mineral rights and concessions in exchange for “services” rendered, McDowell argues.

Such “deals” are creating a scenario in which Russian claims to a host of resources, many vital for the production of electric batteries and other next-generation technologies, are dependent on governments’ good will that Moscow is ill-equipped to stay in power, the analyst warns.

Russia’s incursions into the continent riches have seen state-owned companies targeting key commodities, such as gold, coltan, cobalt and diamonds.

Russia has moved to take advantage

of a desire by African countries — which, notably, are the largest voting bloc

in the United Nations — to lessen their reliance on China. The strategy has, so far, worked, even with President

Vladimir Putin acknowledging his administration cannot come close to matching

Beijing’s financial firepower.

According to official figures, Russia’s

annual volume of its trade with Africa has doubled to $20 billion over the last

five years, but that still pales in comparison to the continent’s $300 billion

in trade with the European Union and $60 billion with the United States in

2018.

Moscow’s focus on the continent riches has seen state-owned companies scaling up their activities in the resources sector, particularly in the search and production of coltan, cobalt, gold and diamonds.

In Zimbabwe, for instance, a 2018

joint venture between Russia’s JSC Afromet and Zimbabwe’s Pen East began developing

one of the world’s largest deposits of platinum group metals.

In Angola, diamond giant Alrosa (MCX:ALRS), the world’s top producer by output, increased its stake in local miner Catoca to 41%, which provides the Russian company with a production base outside the home country.

Private energy giant Lukoil is

reported to have projects in Cameroon, Ghana and Nigeria and be looking to

acquire a stake in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

Russia is also offering nuclear

power technology for several African countries, including the construction this

year of the first nuclear plant in Egypt, financed by a $25-billion loan.

The main risk related to Putin’s

ongoing strategy in Africa, McDowell says, is who would own the resources

targeted by partnerships if local allies give Russia their back.

“Guinea is an example of the

potential downside for Russia if local allies fail. Prompted by Guinea’s

importance as a supplier of bauxite for Russian aluminium producer Rusal,

Russian diplomats in the capital, Conakry, have openly supported President

Alpha Condé’s efforts to extend his term in office; this has helped fuel months

of increasingly bloody civil unrest,” McDowell notes.

Presidential and legislative

elections in Guinea are due in 2020, and China is also competing with Russia

for access to its bauxite and iron ore deposits. A scenario could arise, the

analyst warns, where a new leadership could challenge or reverse mineral deals

agreed by President Condé.

At that point, who “owns” Guinean

bauxite or iron ore would become a matter to be disputed globally, with

consequences to be seen, McDowell concludes.