The United States’ Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is planning to relax two Obama-era rules on how power plants store waste from burning coal and release water containing toxic metals into nearby waterways.

The move, which environmental groups say would prolong the

risk of toxic spills or drinking water contamination, would also give

coal-fired plants up to three extra years to decide how to get rid of their toxic

ash and close unlined residual ponds.

The biggest benefits from the proposal to scale back two

rules adopted in 2015 would come from the voluntary use of new filtration

technology.

The announcement is the latest in a series of moves the Trump administration has taken to try and help the country’s ailing coal industry.

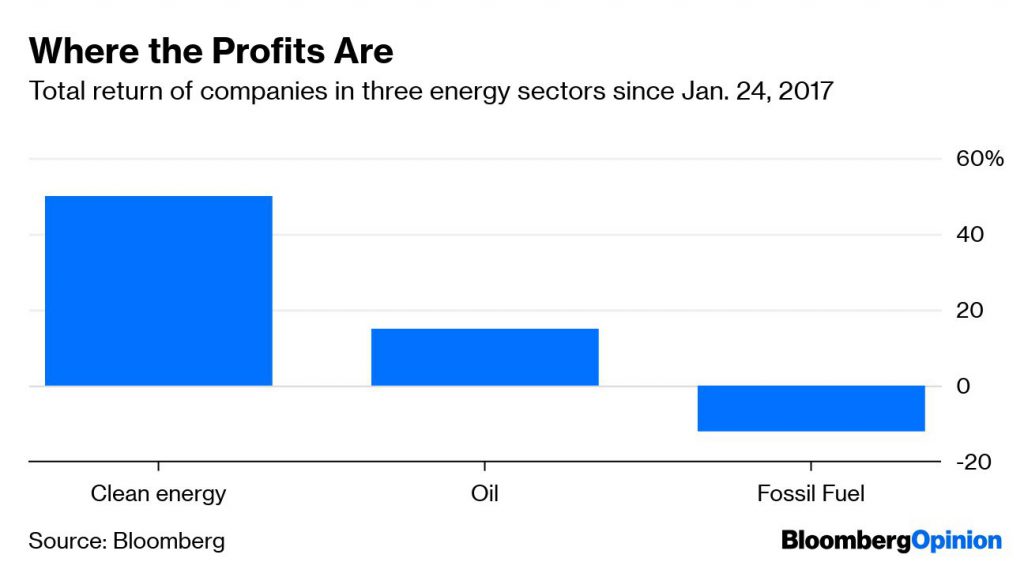

The deregulatory push, however, has been unable to offset

market forces. Coal just can’t compete with cheap natural gas and the falling

cost of solar power, wind and other forms of renewable energy.

US coal exports are estimated to have dropped to 20.9

million tonnes in the third quarter, according to the country’s Energy

Information Administration (EIA). That represents a 28% fall compared to the

same period in 2018.

Internal demand for the fossil fuel, in turn, has hit a decades-low point with power plants expected to consume less coal next year than at any point since President Jimmy Carter was in the White House, according to government forecasts released in early October.

As this transition to renewables continues, Mary Anne Hitt, senior director of Sierra Club’s Beyond Coal campaign, told MINING.com, state and federal lawmakers should take action to protect the miners and communities that have long shouldered the industry’s burdens.

Hitt noted that should be done by “supporting pensions and

investing in a more diverse and robust economy, not bailing out political

donors.”

Coal ash is known to contain several heavy metals and other

toxins including arsenic, mercury and cadmium, all of which have been linked to

a number of health problems. Some of it is stored in dry form or as wet slurry

in ponds. It can also be used as a substitute for soil or as fill material in

construction.

Significant coal ash spills in recent years have drawn attention to the dangers of the residual and its disposal. In 2014, a Duke Energy plant in North Carolina released millions of liquid ash from a shuttered plant. And last year, Hurricane Florence triggered the closure of another Duke plant — the L.V. Sutton station — after the breach of its coal ash stockpile. Slurry there seeped into the Cape Fear River.