Mining executives across the globe believe

their efforts towards effectively reducing the sector emissions and those of

their clients will be key to keeping their licence to operate, as governments become

more involved in curbing risks associated to climate change.

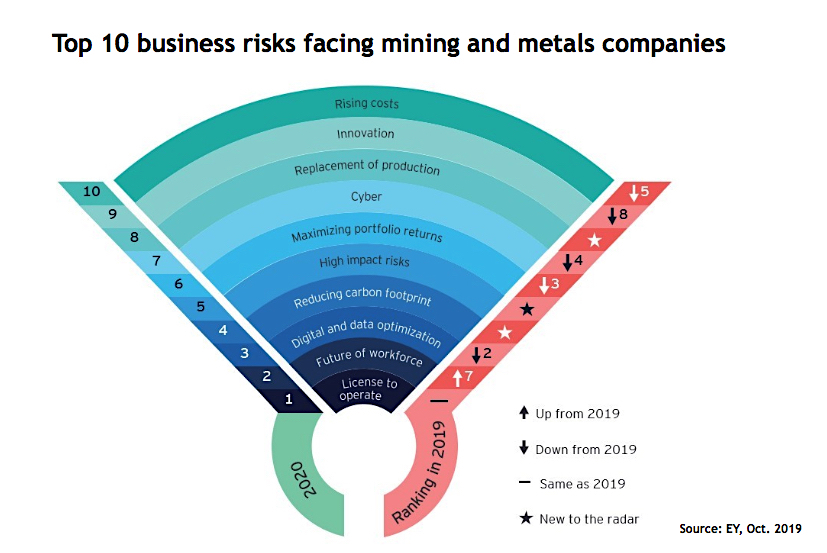

Losing social support, or social licence to operate (SOL), is in fact seen as the main risk mining and metals firms are facing these days, an annual study published by consultancy Ernst & Young (EY) shows.

This is the second year straight that nearly half (44%) of global mining and metals executives rank the topic as the No. 1 threat to their business, showing an important shift in the industry from profit to social responsibility.

This is the second year in a row that global mining and metals executives say that no longer having a social licence is the No. 1 threat to their business.

“Increased stakeholder pressure and the rise of ethical (environmental, social and governance — ESG) investing continues to keep license to operate top of mind for the sector in Canada and abroad,” Jeff Swinoga, EY Canada Mining & Metals Co-Leader, says.

The mining and metals sector is

facing greater scrutiny from end consumers, demanding a transparent ethical

supply chain, as well as a lower carbon footprint.

Shareholder activists are driving

many miners, particularly those with coal assets, to reshape their portfolios

by either reconfiguring existing operations or executing divestments.

“Companies must show how

they’re working towards sustainable and inclusive growth to redefine the

sector’s image as a responsible source of the world’s minerals. Demonstrating

these values is also key to addressing growing workforce challenges,” Swinoga

notes.

EY recommends mining bosses to

start focusing on their “scope 3” emissions – those made by its customers.

‘If mining and metals companies are going to understand their exposure to climate-related risk and capitalize on the opportunities of the transition to a lower carbon economy, then it is inevitable that they will need to properly account for their scope 3 emissions,” the report says.

“Mining and metals companies will have to assess the markets they sell to and consider the impact of selling to customers who produce substantial emissions in the use of their products,” it adds.

Among the other risks mentioned by

the mining executives interviewed, “future of workforce” rose from 7th to 2nd

place in the ranking due to increasing demand for and difficulty attracting the

digital and data-related skills needed to support the future of mining.

“Digital and data

optimization” fell one place but held its position in the top three

business risks cited by miners as they grapple with how to unlock the most

value from investments.

Beyond the “Greta effect”

EY’s survey comes barely a week after the world’s second largest miner, Rio Tinto, signed a pact with China’s biggest steelmaker Baowu to develop and implement ways to reduce carbon emissions in the steel sector, which is responsible for about 9% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

It also comes on the heels of environmental activist Greta Thunberg’s searing address at the United Nations last week, in which the 16-year-old chided world leaders for not doing enough to address climate change.

Thunberg emphasized the urgency of

the global situation, referring often to figures from a seminal report released

by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in October 2018 on the impact of 1.5 degrees Celsius

of global warming.

The document stated that the planet

has already warmed by 1 degree Celsius since the 19th century, and used 1.5

degrees as a threshold beyond which the effects of climate change, such as

melting ice, extreme heat and sea-level rise, become life-threatening for tens

of millions of people around the world.

Reducing global CO2 emissions by half in ten years, as the almost 200 nations that signed the Paris Accord in 2015 agreed, may not be enough.

“Mathematically and technically, it is possible, but it’s not realistic,” Simon Donner, a climatologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, said in a piece published Tuesday in Policy Opinions magazine. “To reduce emissions that sharply in what is now only a 10-year period would take enormous changes in countries around the world.”