While is a known fact that electric vehicles (EVs) use about

four times more copper than gasoline-powered vehicles, short-term demand for

the metal won’t come from the car industry, but from the charging stations and

related infrastructure that need to be in place to support EV growth, a new

study shows.

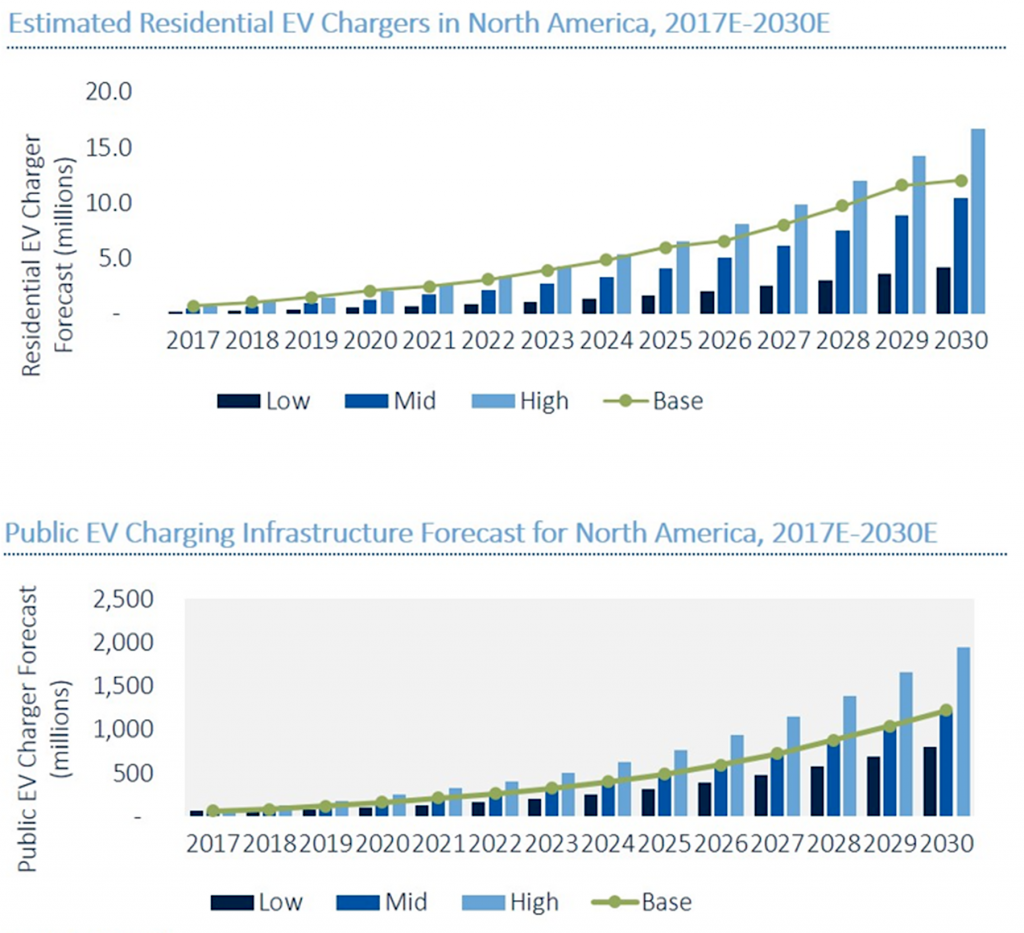

According to Scottish consultancy Wood Mackenzie, there will be more than 20 million EV charging points by 2030, consuming over 250% more copper than in 2019. But such forecast would only become reality if more private and public investment is allocated to it.

The EV charging infrastructure ecosystem is very complex,

and most projects require strong partnerships between both public and private

stakeholders to deploy necessary infrastructure, the research notes.

“Range anxiety – worrying that a battery will run out of power mid-journey – is a key psychological barrier standing in the way of more widespread EV adoption .”

Henry Salisbury, Wood Mackenzie.

No only electric utilities, but equipment makers, software and

network providers, as well as governments and non-governmental organizations

will need to join efforts, the report says.

In North America alone, the EV infrastructure market will total $2.7 billion by 2021 and $18.6 billion by 2030, according to the report.

“By 2040, we predict that passenger EVs will consume more than 3.7 million tonnes of copper every year. In comparison, passenger internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles will need just over 1Mt,” says Henry Salisbury, WoodMac research analyst. “If we look at cumulative demand, between now and 2040 passenger EVs will consume 35.4Mt of copper – around 5 Mt more than is required to meet current passenger ICE demand.”

Currently, less than 1% of the world’s vehicles are

electric, but by 2030 EVs are expected to make up approximately 11% percent of

new car sales.

Consumption from the car industry will also weigh on demand,

but later. An average gasoline-powered car uses about 20 kg of copper, mainly

as wiring. A hybrid needs about 40 kg and a fully electric car has roughly 80

kg of copper (176 pounds).

The amount goes up as the size of the vehicle increases. For

example, a fully electric bus uses between 11 and 16 times more copper than an

ICE passenger vehicle ‚— depending on the size of the battery and the actual

bus.

It means that, in the next decade, global copper demand will increase between 3 and 5 million tonnes, experts seem to agree. Once electric vehicles become popular, they estimate demand to reach 11,000,000 tonnes of new copper for EV’s alone, with potential upside in other green technologies.

Practical and psychological barriers

While EVs are getting cheaper and able to go farther on a

single charge, car shoppers face the challenge of being able to charge their vehicles

on long trips.

Gas stations are everywhere, the process of refuelling is

fast and there’s rarely any need to plan this kinds of stops ahead of time.

EV charging stations are far from being that common. Despite advances in charger and battery technologies, it still takes much longer — about 30 minutes with today’s fast chargers — to recharge a car battery than to fill up the tank.

“As it stands, range anxiety – worrying that a battery

will run out of power mid-journey – is a key psychological barrier standing in

the way of more widespread EV adoption,” WoodMac’s Salisbury says.

“One way to address this is to roll out more charging

infrastructure. As this happens, more connections to the electrical grid will

be required and more copper will be needed as the network expands,” he notes.

The expert also believes copper will benefit from the fact

that there are not viable alternatives to it. The metal’s physical properties

make it the best to conduct electricity and it can comfortably accommodate the

higher temperatures common to EVs.

“Aluminum is the closest alternative,” Salisbury says. “However,

despite it being lighter and almost three times cheaper, copper comes up trumps

on size and efficiency. An aluminium cable needs to have a

cross-sectional area that is double the size of any copper equivalent to

conduct the same amount of electricity.”

Copper is also a key element in green technologies and

renewables, which despite being adopted at a fast pace, still represent

only a minor percentage of the world’s total energy production.