“A currency war, fought by one country through competitive devaluations of its currency against others, is one of the most destructive and feared outcomes in international economics.”

So says James Rickards in his bestseller, Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis. Written in 2011, Rickards’ book feels particularly prescient today, given China’s recent devaluation of its currency against the U.S. dollar—just the latest volley in the two economies’ escalating trade tensions.

The idea of a currency war “revives ghosts of the Great Depression, when nations engaged in beggar-thy-neighbor devaluations and imposed tariffs that collapsed world trade,” Rickards continues. “Nothing positive ever comes from a currency war.”

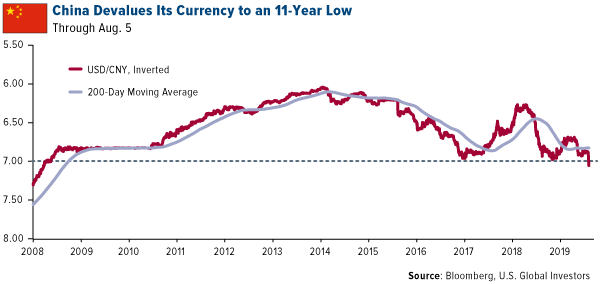

Be that as it may, China’s central bank on Monday allowed its currency, the renminbi, also known as the yuan, to weaken past 7.0 versus the dollar, a level unseen since 2008. A weaker currency gives China certain advantages over the U.S., including making its goods more competitively priced for foreign buyers.

The move follows President Donald Trump’s announcement that the U.S. will be imposing an additional 10 percent tariff on the remaining $300 billion of imports from China, effective September 1. This is on top of the 25 percent tariff that’s already in place on $250 billion worth of Chinese-made goods.

Global stocks sold off dramatically on Monday, as investors interpreted China’s decision as a sign that the trade war between the two countries is far from over. Late in the day, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin made the bold move to designate China as a currency manipulator, writing that the purpose of the devaluation “is to gain unfair competitive advantage in international trade.”

It’s the first time since the Clinton administration that a country has been slapped with the label. It also makes good on one of Trump’s campaign promises, if you can remember that far back.

Beijing Turns It Up to 11

According to Julian Evans-Pritchard, senior China economist at Capital Economics, Beijing “has effectively weaponized the exchange rate, even if it is not proactively weakening the currency” through direct intervention. The research firm sees the renminbi ending the year even lower at 7.3 to the dollar.

Meanwhile, Cowen Washington Research Group’s Chris Krueger, managing director of macro, trade, fiscal and tax policy, called China’s retaliation against Trump’s tariff threat “massive,” adding that “on a scale of one to 10, it’s an 11.”

Capital Economics’ Neil Shearing went even further than his peers in alerting investors and consumers of the potential risks. In a note to clients, Shearing warned that the tit-for-tat trade war poses the biggest obstacle yet for the spread of globalization, which has been the defining characteristic of the world economy in the post-World War II era.

“We may be witnessing the end of the world as we know it, Shearing wrote.

Soy Sales Suspended

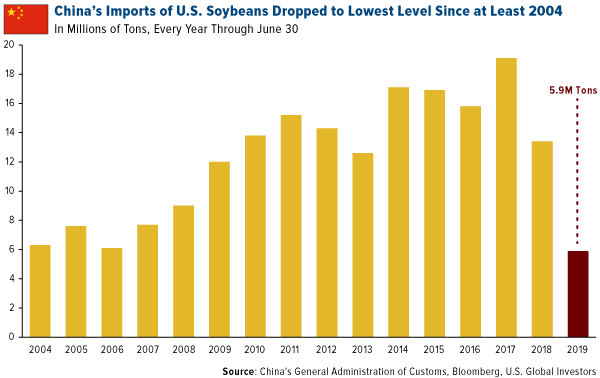

China has gone further than devaluing the renminbi. According to reports, the government has instructed its state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to completely suspend purchases of U.S. agricultural products. No more soybeans, no more cotton, no more hides and skins, grains, pork or dairy products.

This is expected to put even more pressure on already-hurting American farmers.

In the first six months of 2019, U.S. soy exports to China stood at 5.9 million tons, down a whopping 70 percent from the same period two years earlier, and its lowest level since 2004. The Asian country has for years been the number one buyer of American soy, among other major agricultural commodities, but has more recently turned to South American countries, including Brazil, for its supplies.

And as I’ve already shared with you, China—for the first time in about a decade—fell from its spot as America’s top trading partner, according to the Wall Street Journal. Between January and June of this year, imports from China fell 12 percent from a year earlier, while exports fell 18 percent. The total value of bilateral trade, at nearly $290 billion, dropped below that of both Canada and Mexico.

Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the U.S. has also dried up after accelerating for years. According to the New York Times, the amount China invested in the U.S. fell to $5.4 billion last year, down 88 percent from its peak of $46.5 billion in 2016.

Recession Warning Signal Just Got a Little Louder

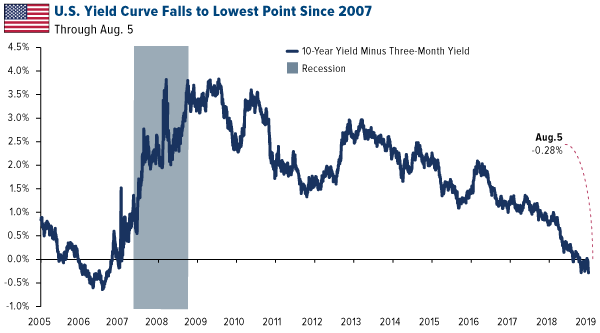

Sharpening trade fears deepened the U.S. yield curve inversion to levels we haven’t seen since 2007. The three-month Treasury bond yielded 28 basis points more than the 10-year note on Monday, the most extreme spread since before the financial crisis.

As the warning signal buzzes a little louder, investors are seeking safe havens, including gold and municipal bonds. The yellow metal traded up 2 percent yesterday, to as high as $1,481 an ounce, a six-year high, and today it’s spiking above $1,485. The next big test is $1,500.

Muni bonds are also rallying. Yields on state and local debt hit their lowest since at least 2011 in the biggest one-day move since April. Like Treasuries, muni yields fall as prices rise. As I’ve pointed out before, munis have done well historically, even in times of geopolitical and economic turmoil.

I’ll have more to say on trade and gold in this Friday’s Investor Alert. Get it before anyone else! Subscribe for free by clicking here!

All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor.

A basis point, or bp, is a common unit of measure for interest rates and other percentages in finance. One basis point is equal to 1/100th of 1%, or 0.01% (0.0001).