Brazil’s right-wing President, Jair Bolsonaro, has issued a new decree that returns the decision-making power of indigenous reserves demarcation to the Ministry of Agriculture, effectively removing any involvement of the National Indigenous Affairs agency (Funai) in the matter.

The country’s lower house of Congress had rebuffed in May the

exact same measure, keeping land decisions on Funai’s hands.

The fresh move, considered a concession to the country’s farm lobby, comes only a week after the agency’s president, Franklimberg Ribeiro de Freitas, announced it was leaving the post as he rejected the government’s push to open up reservation lands to commercial activity.

Brazil’s lower house of Congress had rebuffed in May Bolsonaro’s attempt to do the same , keeping land decisions on the National Indigenous Affairs agency’s hands.

A Native descendant, Freitas had previously run Funai until

April 2018, but was let go by the previous government over allegations that he

was “too supportive” to indigenous tribes’ land claims.

Freitas took part on several operations in the Amazon forest

aimed at reducing deforestation by evicting illegal miners and loggers

from the area, an ecosystem with worldwide ecological significance.

While the temporary decree goes into effect immediately, it requires

to be approved by Congress within 120 days. If that doesn’t happen, the order expires.

Bolsonaro, a former Army captain elected last year, has shown

no sympathy towards indigenous people, who make up less than 1% of the

country’s population and live on reservation lands that cover 12% of its

territory.

He has also come up with controversial statements, which have risen concerns among environmental experts, academics and activists.

He has said, for instance, that he wants to open reservation lands to agriculture and mining, even in the Amazon rainforest. He has also vowed to assimilate the country’s 800,000 indigenous people – less than 1% the total population – into Brazilian society.

Climate scientists say Bolsonaro’s intentions could make it impossible for Latin America’s largest

nation to meet its reduced emissions targets in the coming years.

Other issues conservationists are worried about, include

Bolsonaro’s criticism of Brazil’s environmental agencies for blocking or taking

too long to approve mining and energy projects. He has promised to reduce the

wait time to license small hydroelectric plants to a maximum three months,

rather than the decade it can sometimes take.

Brewing conflicts

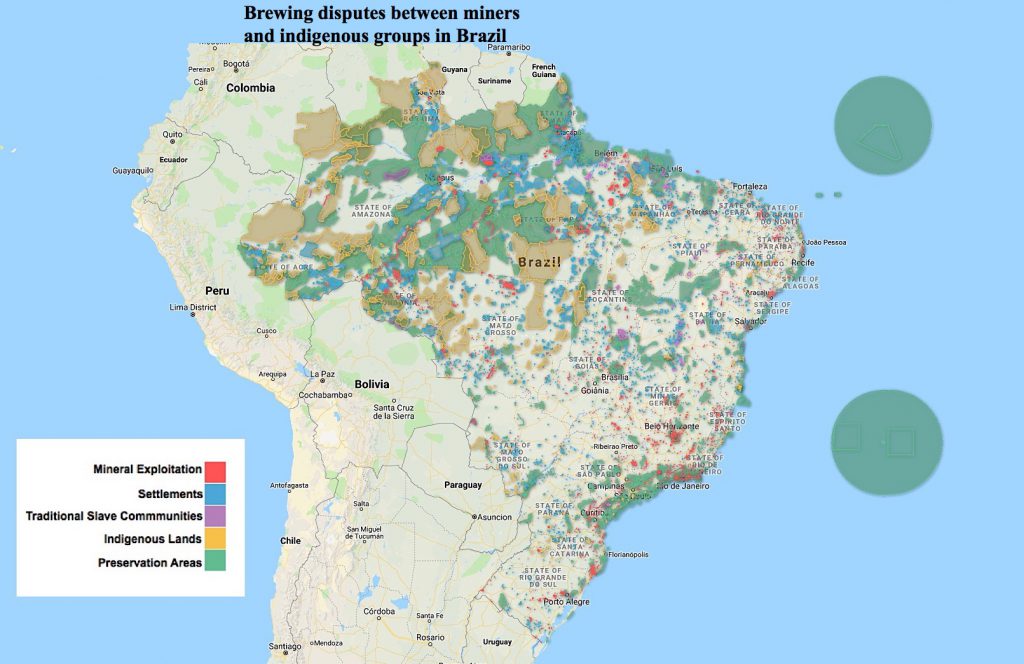

There are over 400 brewing disputes involving mining companies, quilombos (communities made up of the ancestors of runaway slaves) and other indigenous peoples, according to Latentes, a journalistic project to map conflict areas in Brazil.

The investigative reporters found that from the 428

potential conflicts detected in the country, 245 are found in reserves, while

183 involve traditional bondservant communities, as Brazil was the West’s last

nation to abolish slavery.

The mapping crosses data from Funai, the national indigenous

affairs agency, the Palmares Foundation, which regulates quilombos and data

from active mining concession contracts signed by the newly reformed National Mining Agency.

Companies operating and exploring in Brazil are mainly after iron ore (the country is the world’s top producer or the steel-making ingredient) and gold, though the nation also holds large reserves of bauxite, manganese and potash. It’s also Latin America’s No. 1 oil producer.