Source: Rick Mills for Streetwise Reports 09/18/2018

Rick Mills of Ahead of the Herd provides a history of the dollar from its birth as a reserve currency to the pressures it now faces.

Donald Trump will go down in history for many things, including a Justice Department investigation into U.S.-Russian collusion in the 2016 election, a guilty verdict for his former campaign chair, Paul Manafort, and a guilty plea by his personal lawyer, Michael Cohen, in relation to hush-money payments to women in violation of campaign finance laws. Then there was the Access Hollywood tape, the ban on Muslims, the implicit condoning of neo-Nazis, the plans to build a border wall to keep out illegal Mexicans, the separation of immigrant children from their parents (though some say that law was drafted under Obama), and Trump’s ban on global abortion funding to please the pro-life portion of his base. Could Trump’s legacy though be something few had ever predicted: The beginning of the end of the dollar?

On the economic front though, it appears that Trump is doing all the right things. The Dow was at its highest-ever level of 26,616.71 in January, just over a year after Trump took office. The U.S. dollar is strong, unemployment is at its lowest level in 20 years, the stock market is booming, and the Fed thinks things are going so well that it is ready to pass more interest rate hikes. Why has the U.S. dollar done well? Mostly because of high demand for U.S. Treasuries.

Read our Gold and the great stage of fools to learn more about why the dollar is so strong, at the expense of gold, but also why there are cracks in the U.S. economy.

Foreign investors purchased some $26 billion of T-bills in May, driven by fear of a trade war and the indecisive result of the Italian election. They were also attracted by higher bond yields, which hit a seven-year peak in May. The two largest Treasury holders, China and Japan, both increased their buying. Germany bought $12 billion more in April compared to March.

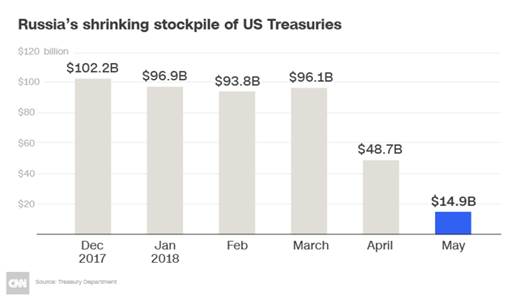

However Russia sold off 84% of its U.S. debt holdings between March and May, leaving just $14.9 billion in its U.S. reserve account. That compares to $102 billion in December 2017. (See graph below). The sell-off corresponded with tough U.S. sanctions imposed on Russian President Putin’s closest associates and Rusal, which produces 7% of the world’s aluminum.

The dumping of U.S. Treasuries by Russia caused barely a ripple among U.S. Treasury officials and politicians, who know that the country only holds about one-tenth of the T-bills owned by China, which has the most of any country, $1.2 trillion. But it begs the question, what would happen if China started selling U.S. Treasuries? The trade war with China is not going well and the evidence shows that China does not need the U.S. as much as it thinks. China is warming to Russia through energy deals and is buying Iranian oil despite U.S. sanctions. Its One Belt, One Road initiative is key to its plan to exert Chinese hegemony and create a trading bloc without the need to trade with its former enemies: the U.S. and Europe. Eventually China could stop buying U.S. Treasuries altogether.

How would that affect the U.S. dollar? And more significantly, how would the U.S. finance its $21.476 trillion debt if the anti-T-bill movement spread and the market for them dried up? Here we trace the origins of the dollar and its post-war pinnacle as the world’s reserve currency, to its current sickly state. Does the U.S. dollar deserve to be the reserve currency, or in the words of former French finance minister and future president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, should it continue to enjoy its “exorbitant privilege”? We think not. This article will explain why.

Birth of the dollar as reserve currency

In July 1944, as Allied troops were racing across Normandy to liberate Paris, delegates from 44 nations met at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, and agreed to “peg” their currencies to the U.S. dollar, the only currency strong enough to meet the rising demands for international currency transactions.

“At the closing banquet, the assembled delegates rose and sang ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.’ The fellow in question was John Maynard Keynes, leader of the British delegation and intellectual inspiration of the Bretton Woods design.” Robert Kuttner, Bretton Woods Revisited

What made the dollar so attractive to use as an international currency, the world’s reserve currency, was each U.S. dollar was based on 1/35th of an ounce of gold (35.20 U.S. dollars an ounce), and the gold was to be held in the U.S. Treasury.

There’s a lesson not learned that reverberates throughout monetary history: when government, any government, comes under financial pressure it cannot resist printing money and debasing its currency to pay for debts.

London Gold Pool

The US began to send larger and larger amounts of dollars overseas to fund its increasing trade deficits. The glut of U.S. dollars held abroad began to threaten U.S. gold reserves—remember U.S. dollars were redeemable for gold—and worldwide demand for gold was soaring. By the late 1950s U.S. gold reserves had began to dwindle rapidly.

“Nineteen fifty-eight marked the first year in which foreign central banks exercised their convertibility rights in significant amounts and returned their dollars for gold. U.S. gold reserves fell 10% from 20,312 metric tons to 18,290 that year, another 5% in 1959, and 9% in 1960.” John Paul Koning, Mises.org, The Losing Battle to Fix Gold at $35

In October of 1960 panic buying caused gold’s price to rise to over US$40 per ounce. A night-time emergency call was made by the U.S. Federal Reserve. The Bank of England was to immediately flood the gold market with enough supply to reduce and stabilize the price of gold. The U.S. had just made it abundantly clear that stopping the drain of its gold reserves, and the depreciation …read more

From:: The Energy Report